This article was originally published at Malaysiakini : https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/451433

SPECIAL REPORT | “When I was a prosecutor, I was for the death penalty. Back then, I just handled the cases mechanically. I mean, all I needed to do was just prove my case and I didn’t really know what happened behind the investigations, behind the cases or behind the stories.

“What I know is that I used the laws and presented evidence to the court and let the court decide. So, I did think people needed to be punished by that back then,” said former deputy public prosecutor Samantha Chong during a recent interview with Malaysiakini.

The judicial system is all about the idea of 'justice'. The judiciary is widely believed to be a mechanism for adjusting the various interests of the society to deliver justice. In other words, through the judicial system, the state can punish wrongdoers and seek redress for victims.

The prosecutor charges criminal suspects on behalf of the state, while judges make decisions according to the law and the facts.

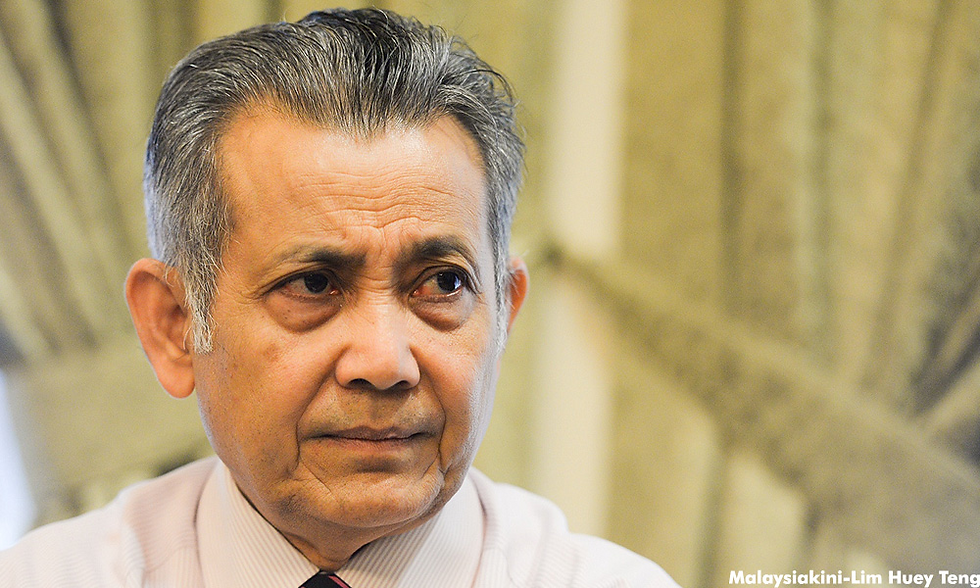

As Mohd Hishamudin Mohd Yunus – a former Court of Appeal judge who has written hundreds of judgments in the past two decades – admits, there is no perfect legal system in the world, although the Malaysian legal system has inbuilt safeguards against the miscarriage of justice.

“We cannot rule out the possibility of the innocent being found guilty. No system of justice in the world is 100 percent perfect. But we can devise a system that effectively minimises the risk of the miscarriage of justice,” Hishamudin (photo) told Malaysiakini.

First, there is the public prosecutor, a highly qualified and experienced legal officer, who sieves through the evidence before deciding whether or not to proceed with the charge that carries the death penalty.

Then there is the High Court judge, a senior judicial officer, before whom the accused is tried. The accused is entitled to be defended by a counsel of his or her choice.

In capital punishment cases, the state provides the accused with a defence counsel if he or she cannot afford to engage one.

Should the High Court find the person guilty, the accused has the right to appeal to the Court of Appeal and thereafter to the Federal Court. Finally, there is the Pardons Board.

All these processes must be gone through before the death sentence can be carried out.

Currently, the state is given the power to put drug traffickers and murderers to death if they are found guilty.

Some believe that putting criminals to death is the best way to achieve justice. Meanwhile, others believe that the death penalty should be abolished, with possible miscarriages of justice being frequently cited as a reason for this stance.

How can the system go wrong?

Ideally, the risk of wrongful conviction should be minimised. But whether this happens in reality is another question altogether.

Chong (photo) has spoken out about the actual circumstances and restrictions faced by enforcers and prosecutors.

The former DPP, who left the Attorney-General's Chambers in 2012 after three years, has changed her position on capital punishment after returning to the private sector.

“I experienced a change of mind after I came back to practice, I can see how evidence can be manipulated,” she said.

The prosecutors only have the investigation paper when they charge someone. They normally do not talk to the witnesses, and do not know how statements are collected. Hence, they do not know whether the witnesses are telling the truth, said Chong.

“We (the prosecutors) were not trained to spot whether the witness is lying or not. Most of the time, we can see that the police officers just ‘copy and paste’ the recorded witness statements or just modify a bit and (then) it becomes the investigation paper.”

Liars, she said, may not be spotted even in court, as the prosecutors are not trained to detect falsehoods. “Demeanour and body language can tell (us) whether a person is lying, but we are not trained on this.”

Chong also stressed that it is a misconception that innocent people will not be convicted. In fact, an innocent person can be sentenced to death because of various factors.

“For example (and this can occur), if you have an incompetent lawyer, a police officer or a prosecutor who is misled to think their mission is to convict you, or a judge who is prejudiced towards you.

“Yes, you can appeal twice but there are so many limitations. In your appeal, you can’t put your version of the story or evidence which was not said in the trial, even if it is true.”

Prosecutors affected by overwork

Chong said prosecutors need to handle a large amount of work on a daily basis and they often work overtime. As such, mistakes can take place.

She added: “To be fair to prosecutors, they don’t actually know whether what was stated in the investigation paper is true. Sometimes, they only find out the truth on the trial date.

“A prosecutor’s task is to present the evidence to the court. There are too many cases in court and too few prosecutors. They are overworked, underpaid and might not have time to go through each investigation paper thoroughly. So, mistakes do happen. ”

Former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak introduced the National Transformation Programme (NTP) in 2009, which aimed to improve the efficiency of the country’s administration and the economy.

Under this programme, Chong said, the police and other enforcement agencies have key performance indicators (KPIs) to achieve. She questioned whether this system actually improved the quality of investigations, however.

“You have to look at the bigger picture. Under the NTP, the police officers and those from other enforcement agencies have a KPI to arrest and to charge and charge a person for a crime.

“If we have this kind of indicator, my question is, will it encourage them to file more charges?”

Impact of fake testimonies

The possibility of fake testimonies sending innocent people to their deaths, as Chong mentioned, is not a theoretical matter. In Malaysia, an innocent man was nearly sentenced to death because of a witness who told a lie.

According to Abdul Rashid Ismail, a lawyer who is experienced in handling criminal cases, S Karthigesu, was charged, tried, and convicted for the murder of beauty queen Jean Perera Sinnappa in 1979. He was the only suspect in that case.

At the time, the main prosecution witness, Bhandulananda Jayatilake, testified that he witnessed Karthigesu exclaim that Jean “did not deserve to live”.

The trial judge regarded these words as an “incriminating outburst,” and Karthigesu was given the mandatory death sentence. There was no evidence found to directly identify the killer and no murder weapon was discovered.

Karthigesu appealed to the Federal Court, but the Federal Court maintained the High Court’s judgment.

Four days after Karthigesu’s conviction, Jayatilake came forward and confessed that he had lied and had not witnessed the alleged incriminating outburst. Subsequently, Jayatilake was convicted of perjury and was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment. The Federal Court then set aside Karthigesu’s conviction and mandatory death sentence.

According to the judgment of the court, Jayatilake had been asked to lie in order to secure Karthigesu’s conviction. Finally, Karthigesu was freed after being on death row for more than two years.

It is evident that miscarriages of justice can take place, such as in Karthigesu's case, and that falsehoods may not be spotted by the police, lawyers and judges. Karthigesu himself may have been lucky, but there may be many others who are not as fortunate as he was.

Under pressure to expedite cases

In addition to the huge workload and pressure to perform that may affect the quality of law enforcement and prosecution in major cases, the pressure of public opinion may also affect the investigation and judicial proceedings.

Ngeow Chow Ying, who is a lawyer and also the executive member of the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network (Adpan), pointed out that the police may be under enormous pressure from the public to expedite the case, and statements may be taken in an inappropriate way during the investigation.

Ngeow (centre in photo) said: “When a major case occurs, do the police handle the case professionally at the crime scene? Do the police maintain the integrity of all the evidence?

“When there is big public pressure, the police may want to close the case faster. They may take the statements from the suspects for a long time, even in an abusive manner.

“There were some foreigners who can’t understand Bahasa Malaysia, and don’t know what was written in the statements, (and yet were) forced to sign it when the police asked them to.”

According to a parliamentary reply dated March 28, 2017, there were 257 deaths in police custody between 2002 and 2016. These real-life cases have raised questions about police procedures during investigations and detentions.

Apart from the police investigation, Ngeow added that omissions could also happen in court proceedings. For example, witnesses may give false statements, or the defence witness may suddenly fail to appear in court at the last minute, and the accused would then be sentenced to death.

“Sometimes, the prosecutor hands the documents for trial at the last minute and the defence lawyer does not have enough time to prepare.

“Sometimes, part of the evidence was destroyed or purposely hidden, and the defendant will not know it. All these situations are quite unfavourable for the defendant.”

'Enough' evidence for conviction

Chong gave the example of one particular case she handled, which allegedly shows that it is possible for part of the evidence or clues to be concealed by the authorities in situations where it may take additional efforts to seek the truth.

According to Chong, a girl was detained by Customs officers on suspicion of trafficking drugs. She told the officer that she had just been helping her friends to send the luggage, and that she had no idea of what was inside.

She gave all the names and contact numbers of those who handed the luggage to her – the real traffickers – to the Customs officers, but was nonetheless eventually convicted, because the investigation officer did not investigate further.

“When the investigation officer was in court, he never actually investigated the names and the phone numbers of the real traffickers that were given to him.

"The answer given is that they think they have already had enough evidence to convict her, so they do not think they should investigate further.

“In this case, imagine that you are in the girl’s shoes. Your friend asks you to send something, you will not open it because you are friends. You gave their names and phone numbers to the enforcement officers and you expect them to investigate. But they don’t, because they think that they have enough evidence to convict you.

“You will not expect to be convicted as you have given the information of the bad guys to them, the judge may then say you need to have their full names, passport numbers, address, and everything…

"What would you think about this?” asked Chong.